“Ōoku”: Yoshinaga Fumi’s Alternative History of a Japan Run by Women

Culture Entertainment History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Reversal in Social Positions

Manga artist Yoshinaga Fumi’s Ōoku (Ōoku: The Inner Chambers) tells the story of an alternative version of the Edo period (1603–1868) in which most of the male population is killed by the Redface Pox, a disease that affects men alone, during the reign of Iemitsu, the third Tokugawa shōgun. Families of peasants, merchants, and samurai lose their breadwinners and heirs, and Iemitsu himself passes away, to be succeeded secretly by his illegitimate daughter. The female shōgun establishes a new society in which men and women’s social positions are reversed. (Spoiler alert: This article discusses the plot of Ōoku, including the ending.)

Japan has long had stories of male-female reversal. Notably, there is the classic work Torikaebaya monogatari (trans. by Rosette F. Willig as The Changelings), written in the late Heian period (794–1185), in which a brother and sister both live passing as the opposite gender, as well as the story’s various manga adaptations. Tezuka Osamu’s 1950s manga Ribon no kishi (Princess Heart) features a protagonist with both male and female hearts, whose personality changes when they are switched. In the 1970s, Oscar, a noblewoman raised as a man, is a main character in Ikeda Riyoko’s landmark manga series Berusaiyu no bara (The Rose of Versailles), set around the time of the French Revolution.

“Yoshinaga Fumi’s Ōoku stands out in that rather than just having switches in appearance, it presents a rereading of history in which men and women’s social positions are entirely reversed,” says manga researcher Yamada Tomoko of the Yoshihiro Yonezawa Memorial Library of Manga and Subcultures at Meiji University.

After Iemitsu’s daughter takes over as shōgun (also using the name Iemitsu), his former wet nurse Kasuga no Tsubone establishes the Ōoku—originally a name for the ladies’ chambers housing his main wife and concubines in the palace, but here with a new meaning—to ensure that her line can continue. This parallels Kasuga’s role in reality, where she was prominent in the Ōoku, except in Yoshinaga’s version of history, the “inner chambers” are quarters for men, chosen for their breeding potential. The country goes into national seclusion to prevent foreign powers learning of the sudden reduction in the number of men. In another reversal, the famous pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara become a place for common women to choose men to father their children. Meanwhile, women perform physical work.

“Instead of suddenly switching male and female roles, Yoshinaga built a plausible, consistent world in which women took on a central position that brought about social change.” Yamada says. “In the end too, the story returns to the ‘real’ history we know. This kind of skillfully constructed story was unprecedented, which I think is why it so quickly won such appreciation both in Japan and overseas.”

Awards and Acclaim

Five years after it began serialization, Ōoku won the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize in 2009, and the following year, it received the James Tiptree Jr. Award (now the Otherwise Award) for science fiction and fantasy works that encourage the exploration and expansion of gender. This was the first time a Japanese writer had won the US award, and also the first time for a comic to do so.

“Alternative histories switching the positions of men and women are common in science fiction. But applying this to the shōgun’s family and the Ōoku got SF readers talking from the start of serialization,” comments science fiction critic and translator Ōmori Nozomi. “I myself was keen to see how this conceit would align with the history of the Tokugawa family, and how Yoshinaga would serve it up.”

In the series, all of the shōguns from Iemitsu to Yoshinobu (the fifteenth and last) appear—Yoshinobu and two others are male—and real history is woven into the story. At the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the burning of top-secret records concerning the Ōoku, covering the history from the time of Kasuga no Tsubone, completes a return to the former social positions for men and women. Saigō Takamori rewrites history to make all the shōguns men, wiping away the “shameful” version produced by women.

“A typical science fiction writer would probably change the names of shōguns after Iemitsu and invent a completely different history of the family that diverges from our history,” Ōmori says. “In Ōoku, though, the major events largely unfold following the history we know, while creating a persuasive alternative. That was a fresh approach.”

The James Tiptree Jr. Award was based just on the first two books in English translation. “More manga was being translated then,” Ōmori continues. “Yoshinaga had a lot of American fans, and news about her story of the Tokugawa shōguns as women spread quickly via word of mouth and blogs. A lot of female science fiction authors read Ōoku in the English-speaking world, too. One notable reader to heap praise on the series was N. K. Jemisin, later a three-time winner of the Hugo Award for Best Novel, who had been a Yoshinaga fan for years.

Says Ōmori: “Science fiction in the United States and Britain, which had been dominated by male writers, has seen a trend in the past few years of female authors producing alternative histories with women as protagonists. One might say that Ōoku was a trailblazer for that trend.”

After the completion of all 19 volumes, Ōoku won the Japan SF Prize in February 2022.

“It wouldn’t have had that impact if it had been a simple alternative history,” Ōmori says. “I feel that the ending of Ōoku won it increased appreciation. It provided an answer at the end as to why, apart from the reversal, there was so little deviation from our history. There’s the shock that our actual history is a version altered by Saigō Takamori. This double reversal provides an amazing finale with that SF-style ‘sense of wonder.’ The stunning revelation reminds me somehow of the end of Planet of the Apes.”

Adroit Rereadings

Born in 1971, Yoshinaga started out by creating parodies of The Rose of Versailles and Slam Dunk in dōjinshi (self-published magazines) before getting her break in the boys’ love genre, making her commercial magazine debut in 1994. She established herself as a manga artist in 1999 with Seiyō kottō yōgashiten (Antique Bakery); the hit series was adapted into a TV drama, as well as a film in South Korea.

“With derivative works, fans can make alterations or connections in the spaces between their favorite stories to make the original more meaningful to them or more fun,” Yamada notes. “For these fan communities, sharing their feelings like this is the biggest thrill. Yoshinaga honed her skills for adroit rereading in her dōjinshi activities.

“When I interviewed her about Ōoku, Yoshinaga said that the story came from an idea she had while at university to write a fantasy about a country ruled by a dynasty of queens. She gave that up after finding it impossible to build a world from scratch. But when she saw a 2003 television drama that was also called Ōoku, she thought that she could write a parody of Japanese history.”

The series includes a section focusing on medical efforts to eradicate the Redface Pox, with an alternative version of “Dutch studies” scholar Hiraga Gennai, portrayed as a lesbian who dresses as a man, and a character called Aonuma, the blond-haired, blue-eyed son of a Dutchman and a female prostitute. While contemporary readers will think of the present battle to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, this part of the story also skillfully adapts real history. Yoshinaga’s narrative draws on the smallpox epidemics that were common during the Edo period, with Iemitsu and other shōguns catching the disease, as well as the development of the smallpox vaccine by British physician Edward Jenner. She also took inspiration from Ebola outbreaks in Africa in the early 2000s.

Rethinking Gender

Yoshinaga chose the setting due to her distaste for how the system ensuring shogunal succession trampled on human feelings.

“Since her debut, Yoshinaga has always considered gender,” Yamada says. “As a period drama fan, she enjoyed the 2003 live-action Ōoku show, but felt the great difficulty of maintaining direct succession through the bloodline.”

Yoshinaga depicts many male-female relationships related to the succession, but in the case of the fourteenth shōgun Iemochi and Princess Kazu, there is a same-sex marriage between two women. Iemochi maintains that a blood relationship is not necessary to be parents, and adopts a child.

Yamada comments, “There don’t need to be male-female relationships. Children don’t have to be related to their parents by blood, and they can be family if they’re raised with love. Yoshinaga’s message to contemporary readers, via the setting of the inner chambers, is that this new kind of family is possible.”

While the history of the female shōguns is erased after the Meiji Restoration, the final scene of the manga offers some hope. In 1871, onboard the ship of the Iwakura Mission, Yoshinaga depicts a conversation between Taneatsu, a fictional character who had been the male consort of a former female shōgun, and the six-year-old Tsuda Umeko. Taneatsu tells the girl how women had once held sway over politics, and encourages her to take on a political role in the future.

In 2007, three years after the start of Ōoku, Yoshinaga began Kinō nani tabeta (What Did You Eat Yesterday?), which continues serialization today.

“I think it’s amazing that a work in a men’s comic that simply shows the everyday life of a middle-aged gay couple has continued to appeal to readers,” Yamada says. “Maybe at first, there was a novelty factor, but now the couple have gone from their forties to their fifties, there’s a feeling that the characters and the readers have got older together.

“For many years in Japan, shōjo [girls’] manga has encouraged consideration of gender and women’s place in the world. Yoshinaga Fumi’s genius emerged from this tradition, and is expressed in Ōoku and What Did You Eat Yesterday? Her drive to persist in creating these engaging works has played a great part in changing readers’ feelings and values.”

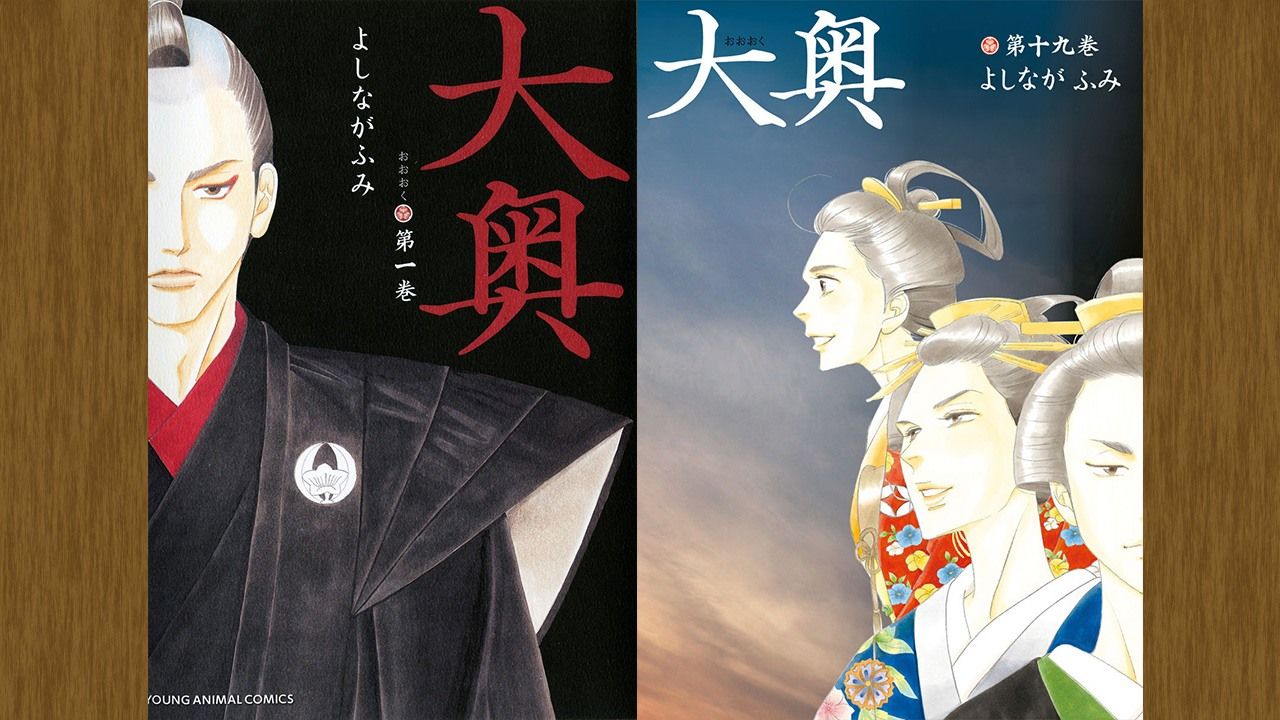

(Originally written by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com and published in Japanese on June 8, 2022. Banner image: The covers of volumes 1 and 19 of Ōoku (Ōoku: The Inner Chambers). © Hakusensha.)

manga Edo period manga artists comics Tokugawa shogunate Manga and Anime in Japan