Espionage and Sabotage: The Truth About the Ninja

Culture Entertainment History Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Ninja Studies Pioneer

Yamada Yūji started his academic career as a specialist in the religious history of medieval Japanese, and his work focused on ghosts and Japanese beliefs about the afterlife. His involvement in ninja studies was the result of a local community initiative launched by Mie University in partnership with the city of Iga, famous as the birthplace of ninja.

Since 2012, Yamada has been at the forefront of a diverse group of scholars from both humanities and science backgrounds who have been working to gain a clearer picture of the truth about ninja using the insights and strengths of their respective fields. The encyclopedic Ninjagaku Taizen (Comprehensive Anthology of Ninja Studies) brings together the findings of this project, shedding new light on the tasks performed by the historical ninja and bringing into clearer focus the true nature of ninjutsu as a compendium of self-defense and survival techniques.

Despite the familiarity of the word around the world today, Yamada says it was only in the middle of the twentieth century that “ninja” became the common term for these figures: “Historically, the commonest term was shinobi,” he says—another Japanese word (忍び) written with the same first character as the compound ninja (忍者). “Different terms like suppa and rappa were used around the country during the Warring States period [1467–1568], but the word with the widest application was shinobi: the secretive, hiding ones. They were active throughout much of the samurai-dominated feudal period, from the Nanbokuchō period [1336–92] of civil war between rival courts right through to the end of the Edo period [1603–1868].”

“In discussing warfare, there’s a tendency to focus on the actions of the generals, but no one can fight a battle without reconnaissance and intelligence. You need to know the topography of the enemy’s position, the condition of his food supplies, the structure of his castle. It was the job of the shinobi to obtain this kind of crucial information. They would infiltrate the enemy domain and ascertain the lay of the land, or sneak into the castle and create chaos through acts of sabotage and arson.”

The Birth of the Shinobi

The oldest mention in the historical record of what we would now recognize as a ninja comes in the fourteenth-century military epic Taiheiki, which tells the story of the period of war between the Northern court backed by Ashikaga Takauji in Kyoto, and the Southern court of Emperor Go-Daigo in Yoshino, in modern Nara Prefecture. In one incident, a particularly skillful shinobi is chosen from among the Ashikaga forces to enter the precincts of the Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine in Kyoto in the dead of night. He sets fire to the shrine precincts, creating panic and chaos in the enemy ranks.

“This use of guerilla tactics, with special agents operating behind enemy lines to carry out acts of espionage and sabotage, is something we see increasingly often in war chronicles from the Nanbokuchō period on,” Yamada says: “Over time, skilled individuals started to specialize in these kinds of operations, and it was from this that the role of shinobi developed.”

The term shinobi is included in the Vocabulario da Lingoa de Iapam, a pioneering Japanese-Portuguese dictionary published by the Jesuit mission in Nagasaki in 1603, where “xinobi” is glossed as “a spy who in times of war enters a castle by night or clandestinely, or infiltrates the enemy ranks to obtain intelligence.”

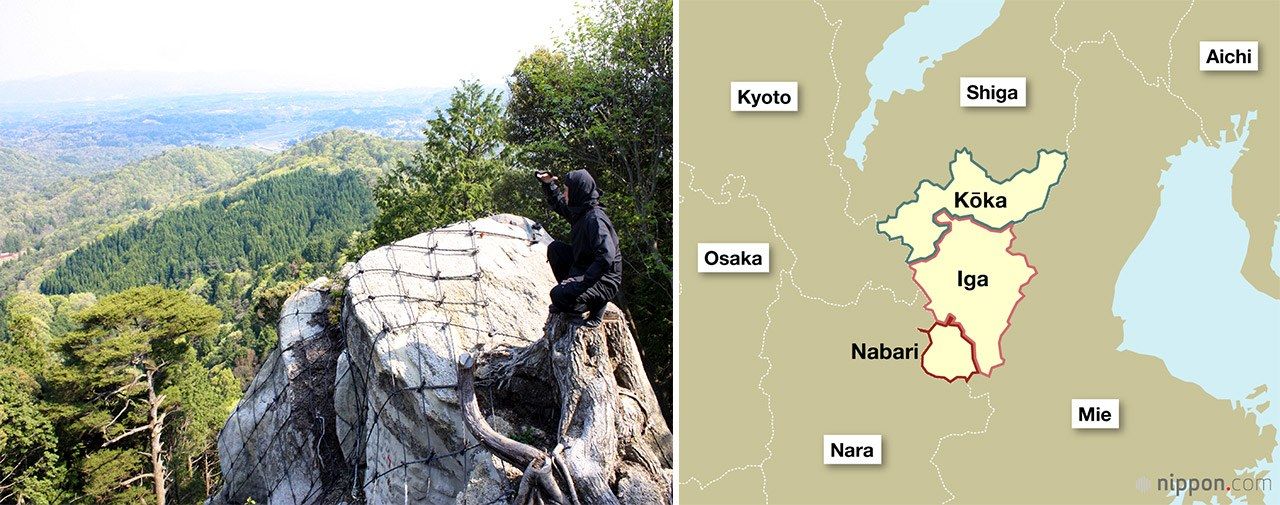

The most famous shinobi of all came from the villages of Iga and Kōka (now the cities of Iga and Nabari in Mie Prefecture and Kōka in Shiga Prefecture). There were reasons for this, connected with the distinctive topography and background of the region.

A modern-day ninja strikes a pose on Mount Iwao in Kōka, Shiga Prefecture. The peak is reputed to have been a training spot for Kōka ninja. (Courtesy Agency for Cultural Affairs; © Jiji) The map shows the cities where ninja were formerly active, along with surrounding prefectures.

There were close ties between Iga and Kōka, fortified by marriage alliances. This is an area of rugged terrain, surrounded by mountains, where the local history and culture were deeply marked by the traditions of shugendō mountain asceticism. It was sufficiently close to Kyoto to make it easy to get hold of the latest news from the capital, but the mountainous terrain meant that secret information was less likely to leak out to the wider world. The authority of the feudal lord hardly extended to mountainous areas like this, and the region developed a strong sense of autonomy. The local people organized themselves into armed bands, and were not afraid to resist central authority. Their skills in guerilla warfare and espionage meant they were often hired by lords from surrounding domains, and many people from this area became shinobi devoted to the dark arts of espionage and subterfuge.

During the Warring States Period, the most important job of the shinobi was to bring intelligence to their lord. For the most part, this meant that they avoided direct involvement in battle. “The strength of the ninja was their ability to outsmart people through subterfuge. If a ninja wanted to infiltrate the mansion of an enemy, for example, rather than sneaking in at night or trying to gain entry via a poorly defended part of the building, he was just as likely to enter in broad daylight through the front entrance, disguised as a merchant or Buddhist priest. He would become friendly with the target, and gather vital intelligence in that way. A ninja needed to have excellent communication skills, and many of the best seem to have had an uncanny ability to persuade people and to manipulate their feelings and thoughts.”

The Legend of Hattori Hanzō

One of the most famous names associated with the ninja of Iga is Hattori Hanzō, or Hattori Masanari. “His name always comes up as a leading soldier and master spearman,” notes Yamada. “His father was from Iga, and it’s likely that he used ninjutsu techniques, but Masanari was from Okazaki in Mikawa province (now Aichi Prefecture). Masanari himself was probably not a shinobi, but rather someone who commanded them.”

When Oda Nobunaga died in 1582 after betrayal by a subordinate, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was in Sakai with just a few attendant warriors, fled across the Iga pass through the mountains to Okazaki in his home domain. It is said that Masanari gave instructions for the people of Iga and Kōka to protect Ieyasu, but there is little historical evidence to support these accounts.

“There are several theories about the route he might have taken. It seems likely that people in Iga and Kōka probably did help Ieyasu get to safety. This was almost certainly the greatest crisis in Ieyasu’s life, but there is no positive proof in the historical sources of Masanari’s involvement.”

But there is no doubt that Ieyasu placed great faith in Masanari. In 1590, Masanari entered Edo (now Tokyo) alongside Ieyasu, and together with men from Iga defended a strategic position on the Kōshu Kaidō route. The Hanzōmon (Hanzo’s Gate) area located just to the west of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo today (previously the site of Edo Castle and home to the Tokugawa shoguns until the Meiji Restoration in 1868), is thought to be named for Masanari, whose Edo residence was located nearby.

The last major event in which the shinobi were actively involved was the Shimabara Rebellion in 1637–38, when thousands of peasants, rōnin, and Christians revolted against the shogunate in an area of what is now Nagasaki Prefecture in Kyūshū. “The shogunal troops sent to quell the rebellion included ninja from various domains around Kyūshū, who infiltrated the castle looking for Amakusa Shirō, the leader of the rebellion, and sabotaged the rebels’ food supplies. A shinobi from the Hosokawa domain in what is now Kumamoto played a particularly important role, setting fire to Shirō’s residence and burning it to the ground.”

A Ninjutsu Encyclopedia

The Edo period marked the end of long years of chaos and turmoil. In the age of peace that followed, the role of the shinobi changed as well. Their most important jobs now were to maintain order and public safety, and to serve as bodyguards protecting the feudal lords.

From around the middle of the seventeenth century, people started to worry that the ninjutsu techniques and skills passed down by word of mouth were at risk of being lost forever. This led to the appearance of several books, which documented the methods and philosophy of the shinobi for posterity. Although these included magical vanishing techniques and other supernatural tricks, many books contain practical wisdom on how to survive and fulfill your duty in conditions of extreme adversity.

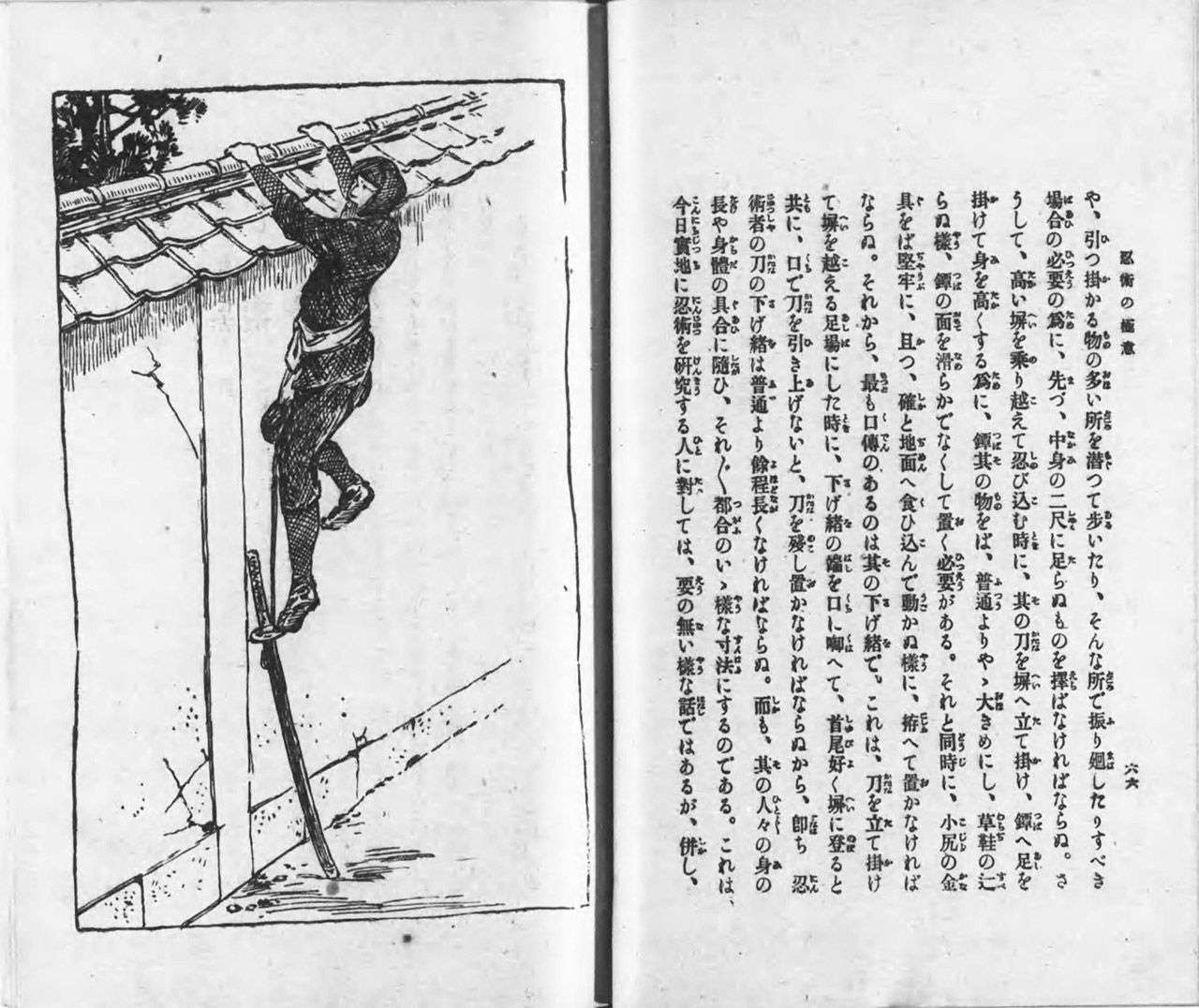

Perhaps the most important of these is Bansenshūkai, an encyclopedia of ninjutsu that was compiled in 22 volumes in 1676, bringing together the most important techniques of ninja from Iga and Kōka. The book starts with a discussion of the state of mind and spiritual practices required of a shinobi, and then records a wide variety of techniques in a range of different areas, including breaking in, sabotage, combat, disguise, diplomacy and subterfuge, and weather forecasting. Many of these derive ultimately from shugendō, including the nine symbolic hand gestures, meditative poses, fire skills, and knowledge of medicinal herbs. The compendium also lists the tools used by ninja, including special grappling devices for scaling walls, rafts for moving across water, and various uses of light and fire. There are illustrations of these items as well as explanations of how to make and use them.

There is also a special section on how to gather intelligence from and about women. There is no record of female ninja historically, and it seems likely that there were no women who specialized in this work. “It is only in fiction from the twentieth century on that we start to see female ninja, but it’s total fantasy,” says Professor Yamada. These books of ninjutsu are a treasure trove of wisdom, much of which still offers useful insights even today.

“The books show that hyōrōgan, the portable preserved food often carried by ninja, included powerful ingredients like ginseng, making it an outstanding superfood with health benefits. A method of breath control called okinaga, or “long breathing,” was effective in encouraging focus and calmness of mind. The books include practical information in a wide range of different fields, from human relationships to medical and pharmaceutical knowledge and insights into the human mind.”

The Art of Self-Discipline

The first lesson of the Bansenshūkai concerns the importance of Seishin, or a pure mind. Ninjutsu must never be used for selfish desires or personal gain. Even after a great success, a ninja must never succumb to pride. He must maintain his spirit of benevolent loyalty. He must monitor his emotions and thoughts at all times, and never yield to selfishness. Purity and self-discipline were of supreme importance to the ninja, who were expected to avoid the temptations of wine and women.

The kanji 忍, found in both shinobi and ninja, consists of two elements: the blade 刃 on top, with the heart or mind radical 心 on the bottom. Yamada says, “The character suggests a mental state of absolute tranquility, in which a person will not flinch even if a bare blade is pressed against his chest. It has two main meanings: to endure hardship with patience, and to perform an act clandestinely. The sense is of a person who undergoes rigorous training and then goes about his dangerous mission in absolute secrecy.”

If a ninja had to die in the line of duty, tradition dictated that he should simply disappear without leaving any trace of himself that would let the enemy discover who he was or where he had come from. Discretion and secrecy were key parts of the ninja’s duty.

Pop Culture Icons

Ninja may have had fewer opportunities for real-life missions during the Edo period, but they became more prominent than ever in the public imagination. They were depicted in a wide range of artistic genres, including kabuki, fiction, and ukiyoe prints. Most people no longer had a clear idea of what the real ninja were like, and this allowed artists to give free rein to their imaginations. It was during this period that the modern image of ninja—dressed from head to foot in black and wielding their trademark shuriken weapon—became established. In reality, a distinctive uniform that made it immediately obvious that a person was a ninja was the last thing any self-respecting undercover special agent would have worn, and there is no record that ninja ever used shuriken in real life.

Particularly popular were stories of ninja spells and narratives about the legendary outlaw hero Ishikawa Goemon, a real-life brigand who was boiled to death in a cauldron around 1594. Later he became the focus of a variety of outlandish tales of banditry and bravado. One story told how he used ninjutsu techniques learned from the ninja of Iga to carry out his crimes; according to another, he managed to penetrate Fushimi Castle with a plan to kill Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

At the end of the Edo period, the era of the real ninja came to an end. But this was far from the end of their popularity. From the late nineteenth century into the twentieth, the phenomenally popular series of Tatsukawa bunko paperbacks turned the character of Sarutobi Sasuke, a Kōka ninja, into a household name, and led to a huge surge in popularity for all things ninja.

In the same period, the writer and critic Itō Gingetsu (1871–1944) was a pioneer of serious scientific studies of ninjutsu as an approach to training the mind and body. He wrote many books on the subject, including Ninjutsu no gokui (Secrets of Ninjutsu), and an essay on “The Ninjutsu,” published in the Japan Magazine in 1918, that is believed to be the first serious information on the ninja aimed at an international readership.

Itō Gingetsu’s 1917 Ninjutsu no gokui (Secrets of Ninjutsu) (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

In the twentieth century, a man named Fujita Seiko (1899–1966), who claimed to be the fourteenth generation of a prominent family of ninja from Kōka, astonished the public by using ninjutsu to demonstrate feats of physical endurance as part of his training to withstand hardship. These included sticking his body like a pincushion with long tatami needles, and swallowing glass. Fujita had a rare mastery of an astonishing array of the arts of war, and taught at the Imperial Japanese Army Nakano School, known for training spies before the war.

From the 1960s, ninja began to appear with increasing frequency in movies, television dramas, manga, and anime.

A Global Phenomenon

American movies played an important part in boosting the popularity of the ninja worldwide. The success of Enter the Dragon in 1973 started a global craze for martial arts movies. One of these was the American movie Enter the Ninja (1981), with Sho Kosugi in a major role. This action movie spawned a long series of successful sequels, and helped associate ninjutsu with martial arts in many people’s minds.

From the 1980s on, Hatsumi Masaaki (born in 1931), head of the Togakure school of ninjutsu and master of a style derived from nine different schools of martial arts, helped to popularize the view around the world of ninjutsu as one of Japan’s many schools of martial arts with an ancient historical pedigree. He has taught martial arts and self-defense to people from police departments and special forces from countries around the world, and his Bujinkan martial arts dōjō in Noda, Chiba Prefecture, attracts students from around the world.

Kawakami Jin’ichi (born in 1949) is the heir of the Kōka Banke ninjutsu school. He too is widely known overseas, and is often referred to as the Last Ninja.

A new image for ninja, particularly among the young generation, was forged in the 2000s by the phenomenal global success of the manga Naruto, featuring a new breed of unique ninja, not least the main protagonist, with his blond hair and bright orange outfit.

A pile of Naruto manga for sale at the International Comic Fair in Barcelona, Spain, in October 2021. (© AFP/Jiji)

Against this global boom in interest for all things ninja, in 2017 Mie University opened a new International Ninja Research Center, and the following year launched the International Ninja Research Association. In September this year, a research seminar will be held at the Chūbu Centrair Airport on the theme, “Taking to the Air: Ninja Around the World.”

The research to date has led to a clearer understanding of the historical truth about ninja, but Yamada says he does not wish to deny the validity of the folk traditions or the diverse range of ideas that people have today.

“I think it’s great that there are so many different ways of approaching the ninja—be it through video games, anime, movies, whatever. I have no intention of being the pedantic spoilsport who comes along and bursts the balloon by telling people, ‘Actually, it wasn’t really like that at all.’ I take a historical approach in my work. I’m an academic historian. But there are many valid approaches to the ninja. I hope people will have fun and enjoy learning about these fascinating figures from our past.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner image © Pixta.)

ninja history Toyotomi Hideyoshi Mie Prefecture Oda Nobunaga Tokugawa Ieyasu