Daikan (Greater Cold)

Culture Lifestyle Environment History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The solar term Daikan (Greater Cold) begins on approximately January 20 in the modern calendar. It is the coldest time of the year, but the days are gradually getting longer as spring approaches. In the ancient calendar, Risshun (Beginning of Spring), which follows Daikan, was considered the start of the year. The day before, the last day of the year, is known as Setsubun, on which it is customary to throw roasted soybeans to dispel evil.

This article will look at events and natural phenomena in the period roughly from January 20 to February 3.

Wakasagi Ice Fishing

The fishing season for wakasagi, or Japanese smelt begins when the ice on lakes and ponds has reached a certain thickness. With global warming, increasingly, lakes do not freeze over, but nonetheless, deep-fried tempura or karaage made with freshly caught wakasagi is considered a seasonal treat.

Wakasagi fishing (left); wakasagi fishing at Lake Yamanaka, Yamanashi Prefecture. (© Pixta)

Winter Food Culture

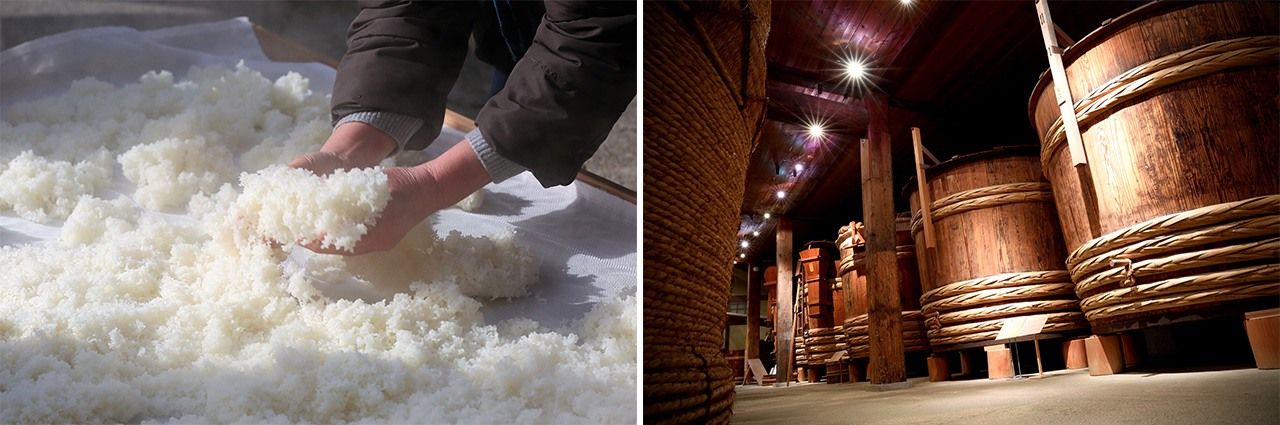

The cold Japanese winter is well suited to fermenting food and beverages such as sake, miso, and soy sauce, leading to the development of this key component of the country’s food culture. Preparing such foods in the cold season inhibits the growth of undesirable microorganisms while allowing for gradual fermentation, said to produce a superior taste.

At this time of year, soba (buckwheat) and rice grains are soaked in chilled water and then dried by exposure to the cold winds in a process known as kanzarashi. This helps to enhance the taste and boost the sweetness. Specialty dishes prepared by such methods include kanzarashi-soba noodles, and a dessert from Shimabara in Nagasaki Prefecture, known simply as kanzarashi, consisting of rice flour dumplings served with sweet syrup.

Sake preparation (left); inside a sake brewery. (© Pixta)

Wintersweet

The wintersweet or rōbai was imported to Japan from China early in the Edo period (1603–1868); thus, in Japanese it is also known as karaume or “Chinese plum.” Although the flowers resemble plum blossoms, they belong to the Calycanthaceae family, whereas plums are in the unrelated Rosaceae family. The yellow petals appear as if made of wax, and the blossoms have a distinctive sweet aroma.

In haiku poetry, this period can be referred to as harutonari (literally, “adjacent to spring”), as an allusion to late winter. Wintersweet and other plants that bloom in the bitter cold are a happy reminder that spring is near.

Daurian Redstart

These migratory birds fly to Japan to pass the winter. They are slightly smaller than sparrows, and the males have a distinctive orange chest. The Japanese name is jōbitaki; the word hitaki means “flint,” and the association derives from their shrill call, which sounds like a flint being struck. Daurian redstarts choose to inhabit residential areas, parks, dry riverbeds, and similar bright, open spaces.

Hatsu Jizō (January 24)

The twenty-fourth of each month is a lucky day associated with Jizō (the bodhisattva who watches over children, travelers, and all those suffering), and thus January 24 is the First Day of Jizō, or Hatsuji Jizō in the new year. Jizō is commonly referred to as “O-Jizō-sama,” a term of endearment, and is generally depicted holding a ring-topped staff in his right hand and a precious orb in the left. Sugamo Jizō-dōri Shopping Street in Tokyo, sometimes affectionately called “Harajuku for Grannies,” has a temple, Kōganji, dedicated to Jizō. Kōganji’s principal object of worship is known locally as Togenuki (“tweezers”) Jizō, after an ancient tale of a miraculous cure. On the temple’s festive days, the path leading to the temple is crowded with stalls selling goods targeted at elderly people.

“Harajuku for Grannies” (Jizō-dōri Shopping Street in Sugamo, Tokyo). (© Pixta)

Setsubun

Setsubun, literally “seasonal division,” was the name used for the last day of each of the four seasons. Later, the Japanese calendar marked Risshun (Beginning of Spring) as the start of the year, and the term Setsubun came to only apply to the last day of winter. On Setsubun, it is customary to throw roasted soybeans to attract good luck and to dispel evil, represented by oni or demons. Afterwards, people eat the number of beans corresponding to their age to pray for good health.

A range of Setsubun traditions exist at shrines and temples across Japan. At Naritasan Shinshōji in Chiba Prefecture and Sensōji in Tokyo, prominent figures who shares the birth zodiac sign of that year are invited to cast a large portion of beans.

Sumō wrestlers Hakuhō and Takayasu throw Setsubun soybeans at Naritasan Shinshōji in Narita, Chiba Prefecture, on February 3, 2020. (© Jiji)

Each year has a lucky direction, known as the ehō, based on a 60-term cycle of the 12 zodiac animals in combination with the traditional five elements. Each Setsubun, it is customary to face the lucky direction and eat a large sushi roll known as an ehōmaki. People who do so should eat the entire ehōmaki in silence while concentrating on their wish for that year. It is said to be derived from the traditional practice of ehōmairi, a New Year’s visit to a shrine or temple which lies in the lucky direction.

Ehōmaki sushi apparently originated as a custom among traders in Osaka in the nineteenth century, to wish for business prosperity. In 1977, a nori (dried seaweed) wholesalers’ association in Osaka launched a campaign promoting ehōmaki, which was picked up by convenience stores and quickly spread throughout Japan.

(Left to right) Soybeans, an oni mask, and ehōmaki sushi. (© Pixta)

Another Setsubun tradition, yaikagashi, involves skewering the head of a grilled sardine on a sprig of holly olive, which is displayed under the eaves near the front entrance of the house. This is because putrid smells and spikey objects are believed to act as a charm against evil spirits.

A yaikagashi decoration: a sardine head skewered on a stick of holly olive. (© Pixta)

Buri (Yellowtail)

Buri or yellowtail is called different names in Japan as it matures. In the Kansai region, the fish is called tsubasu, hamachi, mejiro, and then finally buri. In Kantō, it is called wakashi, inada, and warasa, before maturing into buri. The fish is called buri from around four years of age. Popular serving styles include kanburi (winter buri) sashimi, stew with daikon, or in buri-shabu hot pot.

Buri (left); winter buri sashimi. (© Pixta)

Mizuna

This leaf vegetable was once grown on rows of raised earth without using fertilizer, simply by drawing water between the ridges, leading to its name, mizuna, which translates as “water vegetable.” Because much of it was grown in Kyoto, it is also called kyōna, meaning “Kyoto vegetable.” Traditionally it was used in hot pot dishes or pickled, but because its bitterness and fragrance can eliminate meat or fish odors, it is also used in Western cuisine. The crunchy texture makes it ideal for salads too.

Mizuna (left); harihari-nabe, a hot pot with mizuna and pork. (© Pixta)

(Supervised by Inoue Shōei, calendar researcher and author, Shintō minister, and guest lecturer at Tōhoku Fukushi University. Banner photo: Frost-covered trees on the ski fields of Zaō Onsen in Yamagata Prefecture. © Pixta.)