Know Your “Nihonshu”: Savoring Sake’s Regional Riches

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

(At the counter of a cozy izakaya)

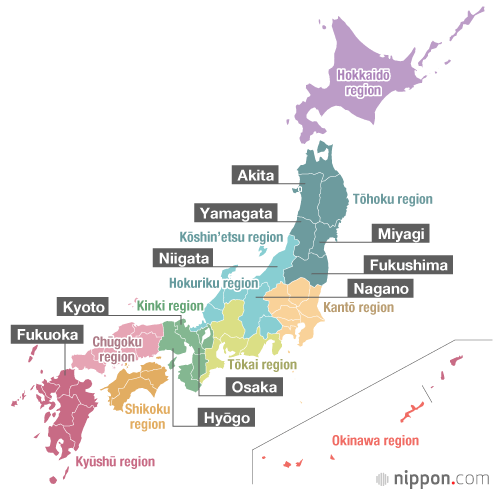

JOE (Gazing at a map of Japan on the wall of the izakaya) Whenever I look at a map of Japan these days, it reminds me of how little of Japan I’ve experienced so far. There’s so much to see between Hokkaidō in the north and Okinawa in the south.

KAORI That’s for sure. Just in terms of climate, we have everything from subarctic to subtropical. And of course, each region has its own history and culture—and sake.

JOE Wow, I really do need to do some more traveling.

KAORI What parts of Japan are you interested in in particular?

JOE Uh . . . what parts of Japan produce sake?

KAORI All of them! There are licensed sake-brewing sites in practically every prefecture.

Climate and Sake Flavor

JOE No kidding! I have this image of sake brewing as something done in a cold, snowy environment.

KAORI Well, you’re right that cold-weather brewing is the norm; it’s called kanzukuri. Sake is usually brewed in a fairly cold environment to inhibit the growth of undesirable bacteria and other microorganisms. It’s also true that some of Japan’s most famous sake-brewing centers are located in parts of the country that get lots of snowfall and benefit from fairly stable low temperatures in the winter. There’s Akita, Miyagi, Yamagata, and Fukushima in the Tōhoku region and Niigata and Nagano in the Kōshin’etsu region . . .

JOE Well, then, I guess north is the way to go.

KAORI Hold on, it’s not that simple! Western Japan is full of excellent breweries as well. The Nada district in Hyōgo has been a preeminent center for sake brewing since the eighteenth century, and even today Hyōgo is Japan’s number one sake-producing prefecture. Number two is neighboring Kyoto Prefecture. Hiroshima in southern Honshū and Fukuoka in Kyūshū also have long, distinguished histories of sake making.

You see, over the centuries, each region has developed brewing processes and ingredients tailored to its own climate, water, and so forth. So, fine nihonshu is made all over Japan, but different regions have different traditional styles.

JOE For example?

IZAKAYA MASTER Why not taste the difference yourself? We have some excellent sake from Niigata and Hyōgo that you can compare for starters.

KAORI Perfect!

MASTER This one is from Niigata, the heart of snow country. See what you think.

JOE Hmm. Dry . . . very light, clean taste . . .

KAORI I agree! Basically, the colder temperatures of the north mean slower fermentation. The cold also inhibits the aging, or maturation, process that takes place after fermentation and pasteurization. So, you get a very fresh, clean taste on the whole. Okay, now let’s try the Hyōgo sake.

JOE Definitely more full-bodied.

KAORI It’s got a deeper umami and a slightly nutty, aged aroma. Hyōgo is at a lower latitude, and the relatively mild winters result in faster fermentation. Overall, you tend to get a more pronounced rice flavor and other complex notes that develop as the pasteurized sake matures over the spring and summer.

Traditional Centers of Sake Production

Traditional Centers of Sake Production

Rice Varieties and Sake Flavor

MASTER Some regional differences also relate to the rice used in brewing.* In the north, the winter comes earlier, so they’ve bred varieties and strains of sake rice that mature more quickly and can be harvested before the cold sets in. The most famous is Gohyakumangoku sake rice, which is the kind used for this Niigata sake. It tends to yield a lighter, cleaner taste. The Hyōgo sake, on the other hand uses Yamadanishiki.

JOE Oh, I’ve heard of Yamadanishiki.

MASTER Well, I guess you know your nihonshu! Yes, Yamadanishiki is very big—the “king of sake rice.” It was originally developed in Hyōgo, and the bulk of production is still in Western Japan, but it’s spreading rapidly, even though it’s considered a late-maturing variety. In a climate like Hyōgo’s, where the weather stays fairly mild right up through October, farmers can wait until the rice is fully mature before harvesting it.

JOE I’m guessing that also contributes to more intense flavor?

MASTER Exactly. Experts also say that sake made with Yamadanishiki matures well after pasteurization, producing rich, mellow flavors. To some degree, brewers in the region seem to have have built their techniques and brand identities around the properties of Yamadanishiki. And these flavors are what sake drinkers in Western Japan have come to expect.

Reveling in Regionality

KAORI Some of my Osaka friends complain that northern sake tastes like water. I guess it’s because they’re used to something richer and more full-bodied. I’m partial to Yamagata sake myself. I like those clean, light, delicate flavor profiles. But I may be a little biased, since my dad’s from Yamagata.

MASTER Nowadays, what with climate-controlled facilities and all kinds of other advances, these regional distinctions aren’t quite as clear-cut as they used to be. But they’re still helpful to keep in mind when choosing a sake.

JOE It’s fascinating. The more I know, the more I want to learn. Hey, Kaori, want to visit some breweries with me sometime?

KAORI How about one of those sake brewery tours they offer?

JOE Great idea. I’ll do some research during the week, and we can start making plans next weekend—if you can fit it in?

KAORI Don’t worry, I’ll fit it in!

*There are more than 100 registered varieties of sake rice (sakamai), that is, sake developed and cultivated specifically for sake-brewing purposes. Technically referred to as shuzō-kōtekimai (literally, “rice suited to sake brewing”), they are distinguished by such brewer-friendly attributes as large kernels and low protein content.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 12, 2018. Banner and illustration by moeko)

- “Nihonshu” Now : Behind the Global Sake Renaissance

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Understanding Sake Brewing

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Types of Sake and Their Characteristics

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Sake Tasting Demystified

- “Nihonshu” Now: Yamagata and the Sake Renaissance

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: Sake Wisdom for Guilt-Free Drinking

- “Nihonshu” Now: Japanese Brewery Senkin Rewrites the Sake Rulebook

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: The Many Faces of Sparkling Sake

- “Nihonshu” Now: Adventures in Creative Sake Pairing

- Know Your “Nihonshu”: How Serving Temperature Affects Flavor

- “Nihonshu” Now: How the Maker of Jikon Turned Mold Into Gold

- Know Your “Nihonshu: Drinking and Serving Vessels

- “Nihonshu” Now: “Jizake” Boutiques Make Sake Shopping Fun

- Know Your “Nihonshu: Let’s Go Sake Shopping

- “Nihonshu” Now: The Source of Kikuyoi’s Quality Runs Deep