Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Mutsuki: Traditional Annual Events in January

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

New Year Beginnings

January, or mutsuki by its traditional Japanese name, is filled with traditions celebrating shōgatsu, the coming of the New Year. As one of the most important celebrations on the Japanese calendar, shōgatsu features a wide range of customs intended to ensure good fortune, health, prosperity, and other auspicious outcomes in the months to come. One practice typically conducted on New Year Day is hatsumōde, the first visit to a shrine or temple.

The origins of hatsumōde are rooted in an ancient ritual known as toshigomori. According to the nonprofit religious organization Tokyo Jinjachō, the rite involved the head of a household secluding himself at the shrine of the clan’s tutelary deity to pray from the evening of the last day of the year to the morning of the first day of the New Year. In time, this marathon session evolved into two distinct customs, a late-night practice observed on New Year eve called joyamōde and New Year Day’s hatsumōde.

The custom of visiting a shrine or temple in the New Year spread through the influence of ehō, an auspicious compass direction that varies each year based on esoteric astrological calculations. By the Edo period (1603–1868), the belief in ehō was such that the first shrine visit of the year was known as ehōmairi, with parishioners using the ehō for the year to determine which shrine or temple to visit and which way to face to greet the New Year gods.

The ehō for any given year is determined by a set cycle of 12 zodiac signs (jūnishi) and 10 calendar signs (jikkan) that were used for such things as marking time and indicating direction.

Jūnishi

| 子 | Rat (ne) |

| 丑 | Ox (ushi) |

| 寅 | Tiger (tora) |

| 卯 | Rabbit (u) |

| 辰 | Dragon (tatsu) |

| 巳 | Snake (mi) |

| 午 | Horse (uma) |

| 未 | Sheep (hitsuji) |

| 申 | Monkey (saru) |

| 酉 | Rooster (tori) |

| 戌 | Dog (inu) |

| 亥 | Boar (i) |

Jikkan

| 甲 | Kō |

| 乙 | Otsu |

| 丙 | Hei |

| 丁 | Tei |

| 戊 | Bo |

| 己 | Ki |

| 庚 | Kō |

| 辛 | Shin |

| 壬 | Jin |

| 癸 | Ki |

The significance of ehō subsequently diminished as Japan constructed its railway network starting in the Meiji era (1868–1912). Trains made it convenient to travel long distances, and railway companies encouraged customers to use their services to visit distant shrines and temples during the New Year season. Eventually, hatsumōde was coined, taking the place of the old term to describe the New Year rite.

January 2 is traditionally the first day of business. During the Edo period, this was when the retail shops in the Nihonbashi district of the capital, in particular the fish market along the river, resumed business after being closed on New Year Day. Called hatsuuri, stores and eateries would mark the event by inviting regular customers to drink and enjoy dishes made with ingredients purchased at the market. Historical accounts describe these as lively gatherings, with shops typically brimming with drunken patrons.

Although the Nihonbashi fish market relocated to Tsukuji following the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake, moving again to its current location in Toyosu in 2018, stores today still observe the Edo-period custom of hatsuuri. Rather than plying patrons with food and drink, though, they entice bargain-searching customers with fukubukuro, “lucky grab bags” packed with an array of mysterious items generally guaranteed to be of greater value than the price paid for them.

The streets of Nihonbashi are thronged with shoppers for hatsuuri in Utagawa Sadahide’s print Ōedo nenchū gyōji no uchi shōgatsu futsuka Nihonbashi hatsuuri (The First Sales on the Second Day of the New Year in Nihonbashi). (Courtesy the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

New Year Entertainment

Japanese New Year television programming typically features light-hearted entertainment by comedians and other performers. Such shows are rooted in the tradition of Mikawa manzai, a type of celebratory performance that originated in the towns of Nishio and Anjō in the Mikawa region of what today is Aichi Prefecture.

The Encyclopedia Nipponica describes the art as being performed by a pair of comedians, a tayū dancer holding a fan and saizō joker carrying a drum, who would go from home to home, making residents and passersby laugh with their comical antics while wishing for the peace and prosperity of households. Also known as Morishita manzai and Bessho manzai, the performance styles vary by region. The genre is recognized as an important intangible cultural property.

A tayū, in his distinctive triangular eboshi hat and hitatare court robes, and a drum-carrying saizō perform for a well-off family in a series of prints by Yōshū Chikanobu depicting daily life in Edo. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

It is unclear how Mikawa manzai came to be associated with New Year celebrations. One theory ascribes it religious significance associated with the traditional Japanese esoteric cosmology of onmyōdō, which was influential during the Edo period. Historical records from Nishio, though, describe it in more plebeian terms, noting that manzai was performed when the gates of Edo Castle were opened for the first time on New Year Day. Performers often visited daimyō residences, indicating that they enjoyed the patronage of the Tokugawa shogunate, whose founder Ieyasu hailed from Mikawa. Anjō was in fact the stronghold of the main branch of the Matsudaira clan, from which Ieyasu descended, and Nishio was held by the Ogyū Matsudaira.

Mikawa manzai remained a regular feature of the New Year into the Meiji era, although its popularity significantly diminished following the fall of the Tokugawa regime. It has enjoyed a minor resurgence in recent years owing to preservations efforts at the local level, including educational programs aimed at children.

A Holiday for Servants

January 11 marks the tradition of kagami-biraki, during which a special rice cake called kagami-mochi is eaten. The round mochi serves both as a New Year decoration and an offering at household shrines and altars. It was thought to be imbued with the power of the New Year gods, and consuming it was seen as a way of sending off the deities and benefiting from their divine force. The rice cake is typically divided and cooked with shiruko, a porridge made from sweetened adzuki beans. The custom, widely practiced today, started among members of the warrior class in the hope of bringing peace and health to the household.

From left: A drawing of an elaborate kagami-mochi displayed at a shop (courtesy ColBase); an attendant at a public bath sits next to a kagami-mochi displayed on a sanbō pedestal, from the 1802 work Kengu irigomi sentō shinwa (Wisdom and Folly Mixed in New Tales of the Bathhouse). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

January 16 is known as yabuiri and was the day that live-in apprentices working for merchant families and others were given leave to rest and return home. This was the first break for such servants, who would have been busily working through the New Year since shops reopened for business on the second.

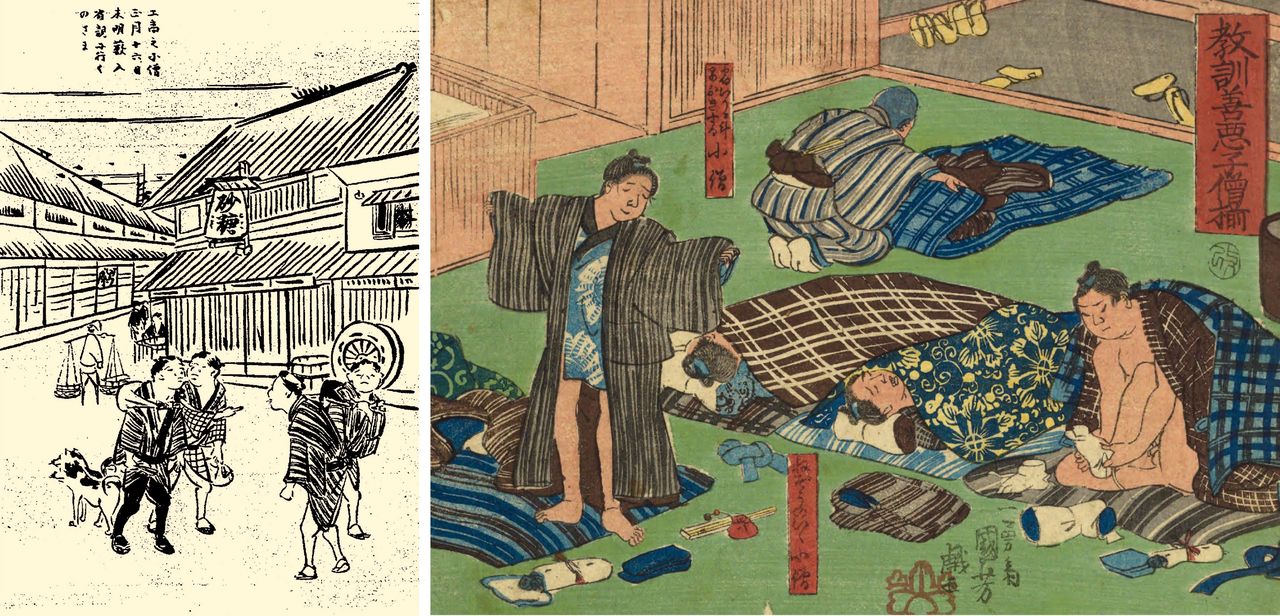

From left: Apprentices return home during yabuiri, as depicted in Kikuchi Kiichirō’s work Edofunai ehon fūzoku ōrai (Picture Book of Edo Customs and Manners); a print showing young apprentices preparing for their day off, from Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s series Kyōkun zenaku kozōzoroe (A Survey of Good and Bad Children). (Both images courtesy National Diet Library)

The number of days off provided to workers varied by employer. The late-Edo-period reference work Morisada mankō (Morisada’s Sketches) describes yabuiri, also known as yadosagari, as a sabbatical lasting “seven days and seven nights.” Servants of samurai households typically received three to seven days off, while their contemporaries at trading houses were generally given just one day, meaning that clerks who hailed from the hinterlands were unable to return home. In such cases, young workers might instead visit the home of a yōfu, or “adoptive father,” typically their guarantor in the city, leading to the custom to also be known as yōfuiri.

In many cases, an apprentice was provided only two holidays a year: one day off for New Year and one for the festival of Obon in summer. Although normal for the time, such employment practices today would be considered slave labor. Not surprisingly, yabuiri disappeared as norms changed and Japan enacted laws protecting worker rights.

Another January custom still observed in many parts of Japan is usokae, a ceremony associated with Tenmangū shrines. The uso, or bullfinch, is connected with the tutelary deity of the shrines, the ninth-century scholar Sugawara no Michizane.

Michizane, the victim of a plot hatched by political rival Fujiwara no Tokihira, was exiled to Dazaifu in Kyūshū in 901. Legend has it that while there he was attacked by a swarm of bees but was saved when a bullfinch drove the insects away. From this story arose the ritual of praying to an image of a bullfinch in the hopes of dispelling the misfortunes of the previous year and assuring good luck in the New Year.

The Dazaifu Tenmangū observes the ceremony on January 7, while the ceremonies at Ōsaka Tenmangū and Tokyo’s Kameido Tenjin and Yushima Tenjin Shrines take place variously on January 24 and 25. Wooden bullfinch figurines called kiuso are popular New Year decorations.

From left: A wooden kiuso as depicted in Morisada mankō (courtesy National Diet Library); workers make kiuso at the Kameido Tenjin Shrine (© Jiji).

Other Traditional January Events

| Event | Day | |

|---|---|---|

| Geigoto-hajime | Jan. 3 | The first rehearsal of the year for traditional performing artists |

| Kemari-hajime | Jan. 4 | A contest of the ball game kemari is held at Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto |

| Jinjitsu | Jan. 7 | Nanakusa rice porridge made with seven herbs is eaten to ensure health in the coming year |

| Tōkaebisu | Jan. 10 | Merchants pray at shrines dedicated to Ebisu, one of the seven gods of fortune |

| Koshōgatsu | Jan. 15 | New Year decorations are taken down and ritually burned |

| Hatsu-Kannon | Jan. 18 | The day for worshipping the bodhisattva Kannon |

| Hatsu-Daishi | Jan. 21 | The first memorial service of the year for priest Kōbō Daishi (also known as Kūkai) |

January contains a wide variety of traditional events, many of which remain part of the seasonal customs observed by Japanese.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: A picture by painter Hanabusa Itchō depicting different New Year customs. Courtesy of the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room.)